Self Portrait (1638/40) by Peter Paul Rubens, KHM, Vienna.

Self Portrait (1638/40) by Peter Paul Rubens, KHM, Vienna.

The Feast of the Bean King (ca. 1640) by Jacob Jordaens, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Death and Maiden (1915) by Egon Schiele, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Solitude (1902) by Karl Mediz, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

The Transportation of Wounded Soldiers (1853) by August von Pettenkofen, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

The Treasurer (1910) by Oskar Kokoschka, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Path in Monet’s Garden in Giverny (1902) by Claude Monet, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Decayed Cemetery in Goisern (1887) by Olga Wisinger-Florian, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Falling Leaves (1899) by Olga Wisinger-Florian, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Flowering Poppies (1907) by Gustav Klimt, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Eve (1881) by Auguste Rodin, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

The Kiss (1908) by Gustav Klimt, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Cottage Garden with Sunflowers (1906) by Gustav Klimt, Belvedere Museum, Vienna.

Tryptich (1991) by Franz Gertsch, Albertina Modern, Vienna.

Winter Landscape (1925) by Franz Sedlacek, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

View of Vernet-les-Bains (1925) by Oskar Kokoschka, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Sleeping Woman with Flowers (1972) by Marc Chagall, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

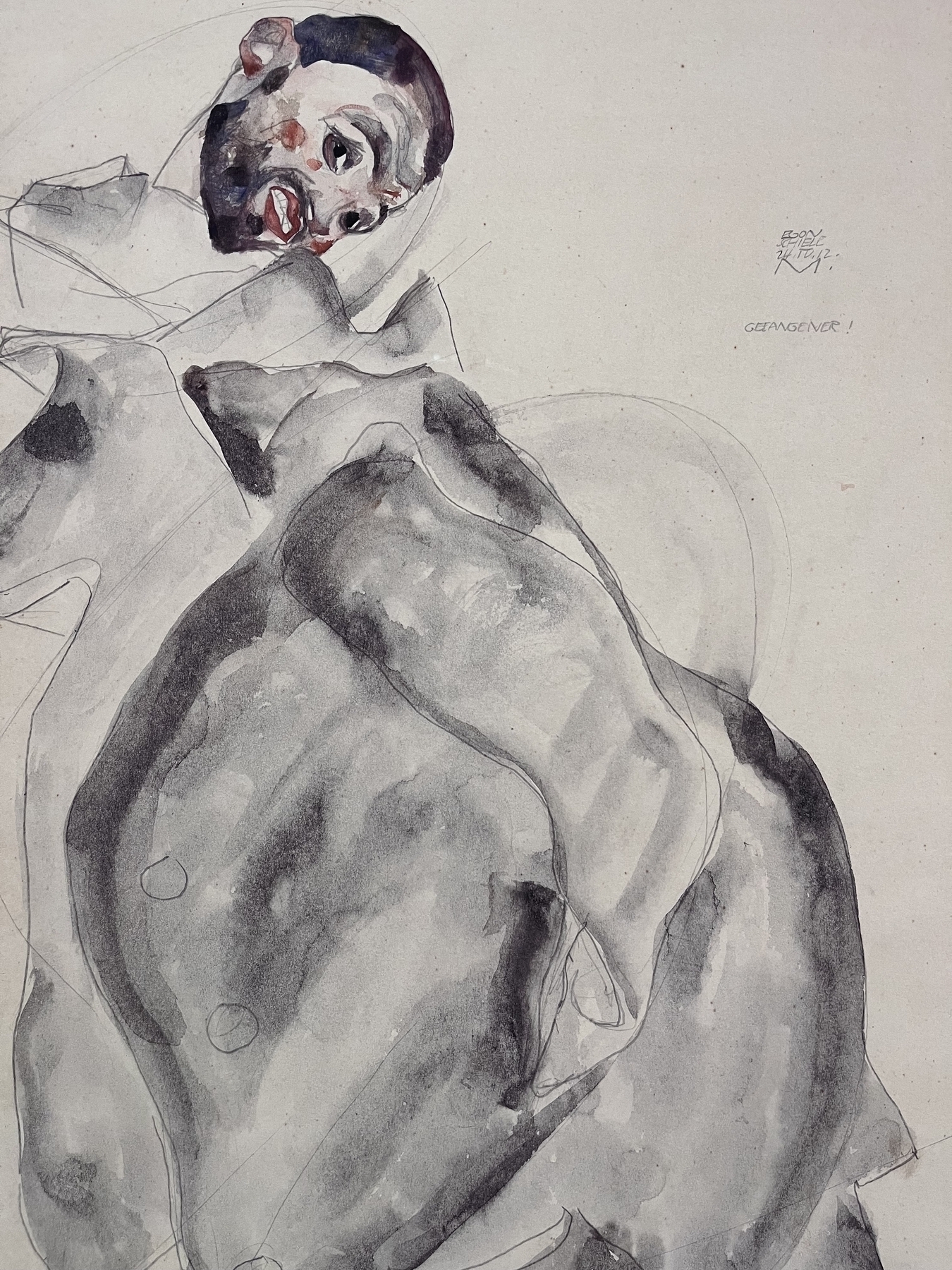

“Prisoner!” (1912) by Egon Schiele, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Four Women on a Plinth (1950) by Alberto Giacometti, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The Golden Horn (1907) by Paul Signac, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

Sunset (1883) by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

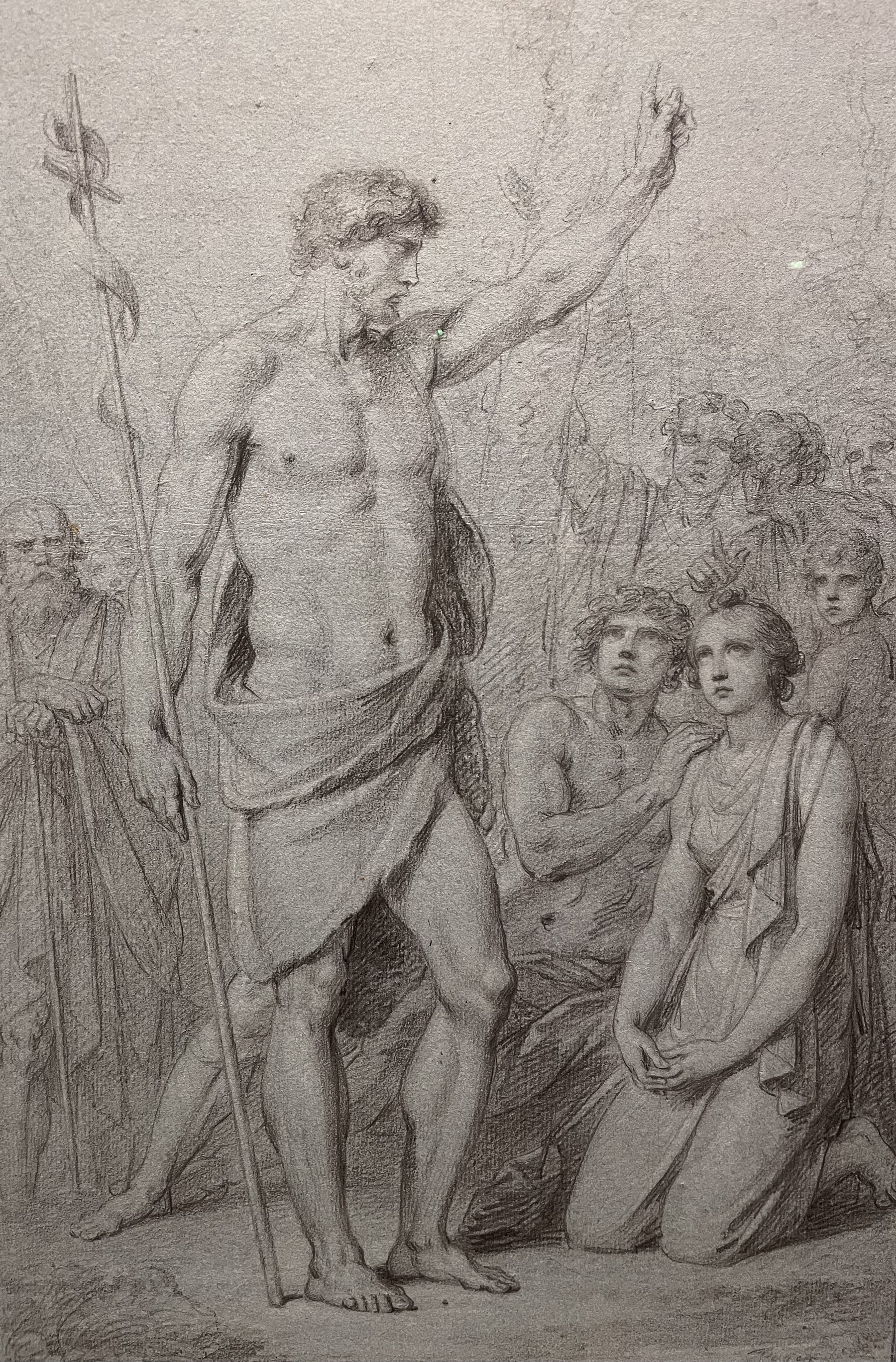

The Human Race Threatened by Water (1804) by Robert Von Langer, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The Entombment (1819) by Robert Von Langer, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The Assassination of Caesar (1810) by Heinrich Friedrich Füger, Albertina Museum, Vienna.

John the Baptist (1802) by Heinrich Friedrich Füger, Albertina Museum, Vienna.